Research

GDR

The story(s) of the Vietnamese contract workers::in the GDR are often forgotten and marginalized. Welcome and indispensable as workers, they lived isolated from social life in the GDR and had little contact with the people of the workers’ and farmers’ state. After the fall of communism, they were thrown into the transformations of the 1990s, perhaps even more radically than the former GDR citizens::ins themselves. Most of them returned to Vietnam, a homeland that had become alien to them. Others sought a place in reunified Germany and are now an important part of our diverse society – but the Vietnamese community still lives isolated and almost in hiding.

Foto: IMAGO / Matthias Rietschel

When the Vietnamese contract workers first arrived in the GDR, many recount their first experience with snow. It was cold in the buses that took them from the airport to the dormitory in the city that was to be their home from now on, thousands of kilometers away from Vietnam. They had never seen snow before.

From the end of the 1970s, the GDR concluded state treaties with so-called socialist brother states on labor migration. One of these was with war-torn Vietnam in 1980. The initial goal was to train the contract workers to rebuild the shattered Vietnam, while at the same time rebuilding the factories there. By the end of the 1980s, some 60,000 Vietnamese were living in the GDR. The contracting parties to the agreements were the states of Vietnam and the GDR, not the workers themselves. They worked primarily in light industry, such as textile and paper processing.

The duration of stay was limited to four to seven years. Initially, training relationships were envisaged, but over time these changed into purely employment relationships due to the labor shortage in the GDR. From 1985 onward, the priority of work over qualification was explicitly agreed upon. Preference was given to single men and women between the ages of 18 and 35. There was no provision for family reunification.

Foto: IMAGO / Roland Hartig

Foto: IMAGO / Werner Schulze

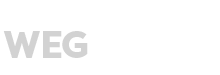

The living situation in everyday life was also regulated by the state. The contract workers were housed separately by sex in dormitories. Married couples were also separated. A living space of 5 square meters per person was contractually agreed upon. The dormitories were equipped with showers, a communal kitchen, heating and a club room and were usually located in the newly built prefabricated buildings, which is described as a special experience on the part of the Vietnamese. There was an obligation to register and deregister in the accommodation as well as a prohibition on visiting. The home’s management had access to all rooms. In case of pregnancy, the only options were abortion or deportation.

Of the wage, 12% was transferred directly to the home countries. Because the GDR mark, as a so-called domestic currency, was not convertible, the contract workers::in sent goods to their home countries; often goods that were in short supply in the GDR itself, such as bicycles, sewing machines and mopeds, which were dismantled into individual parts and sent in parcels.

Foto: IMAGO / Matthias Rietschel

Foto: IMAGO / Werner Schulze

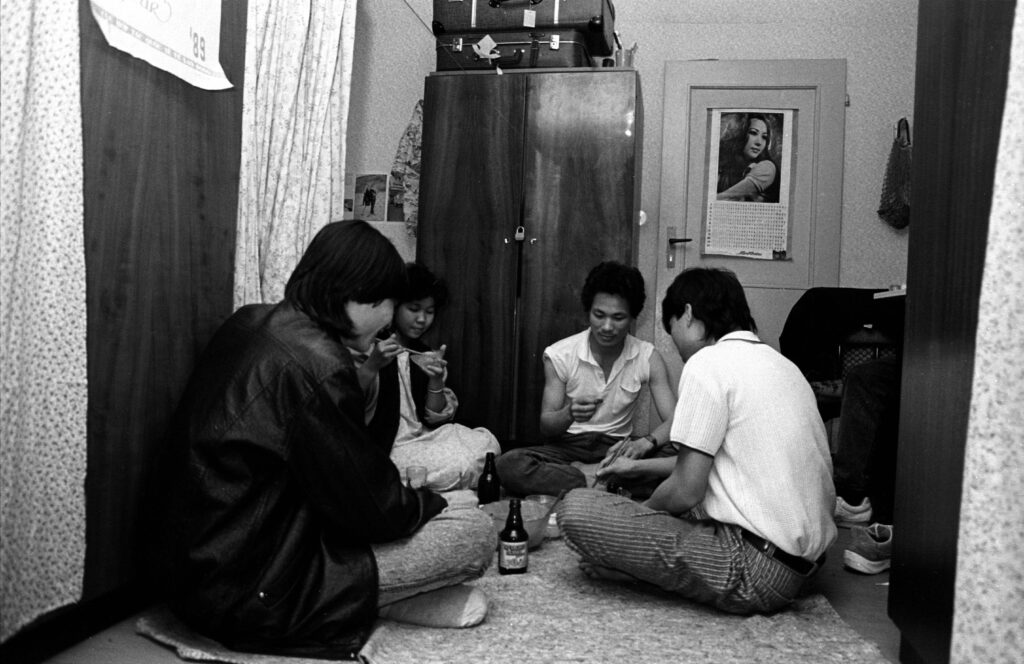

Between the contract workers and the GDR citizens, a kind of double movement developed between visibility in the workplace and simultaneous invisibility in everyday life. In addition, there was the “double bind” of propagated Soviet international solidarity versus the undesirability of contact between contract workers and citizens of the GDR. The foremen of the so-called Volkseigene Betriebe, or VEBs, were advised not to have any personal contact with the Vietnamese.

Between the contract workers and the GDR citizens, a kind of double movement developed between visibility in the workplace and simultaneous invisibility in everyday life. In addition, there was the “double bind” of propagated Soviet international solidarity versus the undesirability of contact between contract workers and citizens of the GDR. The foremen of the so-called Volkseigene Betriebe, or VEBs, were advised not to have any personal contact with the Vietnamese.

Foto: IMAGO / Werner Schulze

The turnaround in Germany

Due to the limited period of residence in the GDR and the desolate economic situation in Vietnam, the Wende years were complicated in terms of residence status. The negotiations for the Vietnamese who wanted to stay in Germany dragged on until the 1990s. 16,000 Vietnamese remained in Germany. Because they were not allowed to work in Germany without a residence permit, they often had to become self-employed to ensure their survival.

Foto: IMAGO / Werner Schulze

In addition, the Vietnamese have been subjected to right-wing attacks in Germany. The best-known examples of this are the riots in Hoyerswerda in 1991 and Rostock-Lichtenhagen in 1992.

Starting from the historical situation, today we want to ask about the experiences and stories of the former Vietnamese contract workers and make the reality of their lives tangible today.